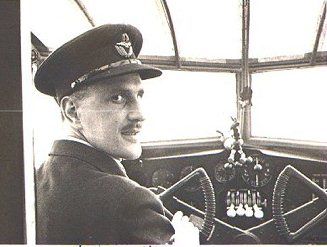

Captain Eric Starling, a later contemporary of Fresson’s, was also heavily involved in opening up the north in the first years of the airlines. He gained notoriety early on in his flying career when, while working as an apprentice for the Redwing Aircraft Company and qualifying for his Commercial licence in 1933, he became lost on a misty night flight across the channel from Croydon to Lympne. Growing anxious and low on fuel, he elected to land along a well-lit street in Calais’, much to the surprise of the residents that lived along the Boulevard des Allies.

Without realising it, Eric had secured his future with the infamy this misadventure

created, as a chance meeting with Aberdeen Airways founder, Gander Dowar, ultimately led to his employment as Chief Pilot for Aberdeen and later, Allied Airways. Gander Dowar had heard of the incident and was much impressed by the ‘enterprising’ nature of the landing. On meeting Starling for the first time and realising who he was, Gander Dowar was famously to have said, “God! You’re as mad as I am. I’m going to build an airport and start airlines at Aberdeen. Are you willing to join me?”

Before Starling went on to work for Gander Dowar’s new airline he began his flying

career proper, in the same way Fresson had, as a barnstorming and Flying Circus Pilot, giving joy-rides and performing displays to local crowds in the South of England and working for little more than beer money. There were already many Flying Circus outfits by the mid-1930’s and competition was stiff, making life as a circus pilot very much a ‘hand to mouth’ existence. The outfit was bankrupt by June 1934.

After writing to Gander Dowar following their chance meeting the year before, he was invited to an interview with him at the Royal Aero-Club and was offered a job. He added the DH84 Dragon to his licence and although flimsy looking to the modern eye, these aeroplanes were state of the art in their day, being twin-engine with an enclosed cabin and able to carry 8 passengers and mail at 150 mph to anywhere in the country. They were to become the workhorse of the regional airlines and continued to be operational in the Air Ambulance role well beyond World War II.

Eric also added the Shorts Scion to his licence, which was to form part of the early

Aberdeen Airways fleet and could carry five passengers, as well as doing an instructor’s

course to help out with Gander Dowar’s flying school at Aberdeen. He travelled up to the North East in the company’s new Scion, ready for the airport’s official opening at Dyce on the 28th July 1934.

He had engine trouble in the Aberdeen Airway’s new Shorts Scion, on a sightseeing trip with some business associates of Dowars as passengers, forcing him to put down in a field of crop. He did a good job of getting the Scion down without damage and after offloading his passengers he and an engineer that had arrived from Dyce, checked the engine over. Finding nothing obvious wrong, Eric took off again to take the aeroplane back to the Airport, only to have more engine trouble. He turned the machine around and attempted a landing back into the same field. Without the passenger’s weight onboard, the aircraft tipped over on its nose as the crop dragged at the heavy front end, though luckily Starling came out unscathed.

This was one of many scrapes that Eric found himself in over the course of his career, though all were more a result of the vagaries of flying in those days than being due to any lack of judgement on his behalf and it is a testament to his flying skill that none of his many mishaps resulted in anything more serious than inconvenience and a higher insurance premium.

The small Deeside town of Banchory, now a visual reporting point for the Aberdeen Air Traffic Control Zone, was the place where Starling found himself having to force land again; this time in Gander Dowars personal aeroplane, the Blackburn Bluebird, an open cockpit bi-plane similar to the more famous De Havilland Gypsy Moth; a gorgeous aircraft and a true classic now.

Eric disliked the Bluebird intensely, describing it as a ‘horrible aeroplane’, being underpowered and prone to spinning if not handled carefully. It was also single engine and by that time, having had numerous scares and forced landings in the company’s Puss

Moth, he had developed a healthy mistrust of anything with less than two engines.

Over the next five years Eric flew all over Scotland as Chief Pilot of Aberdeen and Allied Airways, constantly battling the bad weather of the region, which saw him carry out an emergency landing on a beach in the Moray Firth, with passengers on board and surviving a horrendous flight to Kirkwall through thunderstorms in the fragile Dragon ( where, running low on fuel and lost over the hills of Caithness, he was forced to let out his 30ft long HF aerial in order to get a radio fix on the Kirkwall Beacon, with lightning flashing all around him ) .

Eric played a huge role in opening up the new routes linking Shetland with the mainland during these years and also pioneered the first passenger carrying flights across the North Sea to Norway, but, after getting married in 1939, he took up a post with Brooklands Aviation as a navigational instructor, which afforded him far greater leisure time with his new wife, compared with the relentless six days a week flying of Allied Airways. War, however, was spreading across Europe and he took up a commission with the RAF, continuing initially as a navigational instructor at Brooklands and then Blackpool.

By 1941 he was posted to the long-range reconnaissance squadrons of Coastal Command and carried out U-Boat patrols over the Atlantic from bases in Ireland and then Iceland. From there, he was sent out to Malta and the Western Desert but returned to the UK in 1943 for a brief spell where he converted to the emerging Air Sea Rescue role and after forming a new squadron for this task, was posted out to India for the remainder of the war.

By this time, Eric had a young family and after the war he decided to seek employment again with the regional airlines in Scotland, rather than join many of his other contemporaries in Imperial Airways, having had enough of the long periods of separation.

In 1946 he was employed by Scottish Airways and was based out of Inverness, flying

Ted Fresson’s old Dragon Rapide, an improved version of the DH84 Dragon, on the familiar Shetland and Kirkwall service. He remained with this airline into its British European days, going on to fly the turbo-prop airliners of the 1950’s and 60s throughout Scotland and into Europe, ending his career as a senior managing pilot.

His long career spanned an incredible four decades of flying and for the last three

years he was a full-time Air Ambulance pilot, carrying out his final day’s flying on 06th December 1971 with a grand total of 12,548 hours and 5 minutes flying time.

During his forty years of flying he flew forty-five different types of aeroplane, from

single engine, open cockpit biplanes to the more modern, multi engine airliners of the post war era, seeing the industry change from the risky, ‘seat of the pants’ flying that had characterised the early years, into the routine and safe method of transport that it has become today.

In an interview with Iain Hutchinson for his biography ‘Flight of the Starling’ Eric commented that; “Throughout my airline flying I have been trying to take the adventure out of air travel………………I’ve always done everything to convince the public that

airline flying is humdrum and safe.”

Undoubtedly, along with Fresson, Eric Starlings tireless efforts flying the stormy skies of the North of Scotland in the mid 1930s, when a pilot had to survive very much on his wits and experience, did much to bring the region into the modern age.

i have enjoyed your comments regarding my father Captain Eric Starling. It is worth noting, however, that to my best recolection he never flew for Loganair and retired from BEA while flying ambulance trips after his retirement as Flight Manager Glasgow. Angus Starling angus.starling@virgin.net

Many thanks Angus – it’s an honour to hear from you and Ill certainly correct the text accordingly. Thank you so much for getting in touch.

Angus is correct – Eric never flew for Loganair, but Loganair did honour him naming an Islander after him. Loganair was kind enough to invite him about a couple of commemorative flights. Iain Hutchison (not Hutchinson) iainhutchison.scotland@gmail.com

I recall a 1980 school trip from Papa Stour to Foula on the BN-2, G-BEDZ. My first flight and partly my subsequent inspiration to pursue a flying future. The fuselage bore the name “Captain Eric E Starling”. What could Loganair’s motivation have been to adorn their aircraft thus, unless there was some affiliation history?

Trystan.holtbrook@fly.virgin.com

Hey Trystan – hope you’re good? I can only assume so, yes. Or a case of ‘stolen heritage’ 🙂